The People

94. The Allure of Chanel, by Paul Morand

Morand first met Coco Chanel in 1921, and in 1946 was invited to visit Chanel in St. Moritz, where he had extensive conversations with her, with a view to help write her memoirs. That project never came off, and the notes were put away and did not surface again until after Chanel's death, and were published finally in 1976.

It's pretty well known by now that Chanel created herself in more ways than one, inventing stories about her childhood and upbringing, but the reality of a young woman who broke loose from that past, lived in the era of Picasso and Sert, and changed the face of fashion in a career that spanned the world wars, can't be anything other than fascinating. No longer were clothes designed only for women whose lives were "worthless and idle"; they were for women who led busy lives and who, therefore, needed to feel comfortable in their clothes. Tossing out corsets and introducing menswear tailoring, Chanel anticipated the needs of women as the 20th-century advanced.

Because these are Chanel's own words and thoughts, this book provides an insight into the thinking of a woman who was not only a great couturier, but a woman whose influence still resonates today. I cannot help but be reminded of the Chanel exhibit I saw at the Metropolitan Museum of Art a few years ago. The exhibit juxtaposed Chanel's work with that of Karl Lagerfeld, who became head of the House of Chanel in the early '80s. The difference was stark. Nearly everything of Coco Chanel's could be worn today without hesitation, so classic are they. The designs of Lagerfeld, on the other hand, could have the date of design written on them.

The book is not, however, confined to Chanel and the world of fashion. She talks, also, about her private life, her amours, which would be a book in and of themselves.

Morand first met Coco Chanel in 1921, and in 1946 was invited to visit Chanel in St. Moritz, where he had extensive conversations with her, with a view to help write her memoirs. That project never came off, and the notes were put away and did not surface again until after Chanel's death, and were published finally in 1976.

It's pretty well known by now that Chanel created herself in more ways than one, inventing stories about her childhood and upbringing, but the reality of a young woman who broke loose from that past, lived in the era of Picasso and Sert, and changed the face of fashion in a career that spanned the world wars, can't be anything other than fascinating. No longer were clothes designed only for women whose lives were "worthless and idle"; they were for women who led busy lives and who, therefore, needed to feel comfortable in their clothes. Tossing out corsets and introducing menswear tailoring, Chanel anticipated the needs of women as the 20th-century advanced.

Because these are Chanel's own words and thoughts, this book provides an insight into the thinking of a woman who was not only a great couturier, but a woman whose influence still resonates today. I cannot help but be reminded of the Chanel exhibit I saw at the Metropolitan Museum of Art a few years ago. The exhibit juxtaposed Chanel's work with that of Karl Lagerfeld, who became head of the House of Chanel in the early '80s. The difference was stark. Nearly everything of Coco Chanel's could be worn today without hesitation, so classic are they. The designs of Lagerfeld, on the other hand, could have the date of design written on them.

The book is not, however, confined to Chanel and the world of fashion. She talks, also, about her private life, her amours, which would be a book in and of themselves.

95. D.V., by Diana Vreeland

I really adored this book. It's not written. Instead, it's rather obvious that the editors, George Plimpton and Christopher Hemphill, just sat down with Mrs. Vreeland and let her talk, and then pretty much transcribed the conversation as it had happened. And, boy, can she talk! A mile a minute is a conservative estimate. You zip through this book because you find yourself reading it as quickly as it was said. And it's full of italics! Vreeland's excitement and enthusiasm for whatever it is she's talking about are evident on the page.

What a life she led. Raised in a rawther social family, in London and Paris and New York, she married banker Reed Vreeland at the age of nineteen, and he was clearly the love of her life. She knew everyone, from Josephine Baker to Jacqueline Onassis with the Windsors in between, practically invented red, was fashion editor at Harper's Bazaar for twenty-six years and editor-in-chief at Vogue for eight, and ended her career at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute.

Remarks like "Unshined shoes are the end of civilization" and the famous "Pink is the navy blue of India" make Vreeland seem superficial. And, indeed, she herself said that she adored artifice. But she was also a very insightful, practical, intelligent and hard-working woman. She rightly says that the books one has read are the way you find out about a person. And although she says, "I stopped reading -- seriously reading -- years ago, she can talk about Tolstoy and kept The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon next to her bed. (More on Vreeland's books.)

If Chanel brought fashion kicking and screaming into the 20th-century, it was Vreeland (who adored and patronized Chanel) who made it part of the life of the woman-on-the-street.

I really adored this book. It's not written. Instead, it's rather obvious that the editors, George Plimpton and Christopher Hemphill, just sat down with Mrs. Vreeland and let her talk, and then pretty much transcribed the conversation as it had happened. And, boy, can she talk! A mile a minute is a conservative estimate. You zip through this book because you find yourself reading it as quickly as it was said. And it's full of italics! Vreeland's excitement and enthusiasm for whatever it is she's talking about are evident on the page.

What a life she led. Raised in a rawther social family, in London and Paris and New York, she married banker Reed Vreeland at the age of nineteen, and he was clearly the love of her life. She knew everyone, from Josephine Baker to Jacqueline Onassis with the Windsors in between, practically invented red, was fashion editor at Harper's Bazaar for twenty-six years and editor-in-chief at Vogue for eight, and ended her career at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute.

Remarks like "Unshined shoes are the end of civilization" and the famous "Pink is the navy blue of India" make Vreeland seem superficial. And, indeed, she herself said that she adored artifice. But she was also a very insightful, practical, intelligent and hard-working woman. She rightly says that the books one has read are the way you find out about a person. And although she says, "I stopped reading -- seriously reading -- years ago, she can talk about Tolstoy and kept The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon next to her bed. (More on Vreeland's books.)

If Chanel brought fashion kicking and screaming into the 20th-century, it was Vreeland (who adored and patronized Chanel) who made it part of the life of the woman-on-the-street.

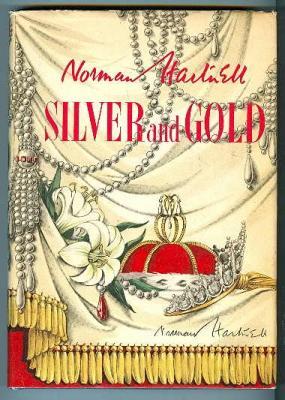

96. Silver and Gold, by Norman Hartnell

Norman Hartnell left Cambridge without a degree, intent on becoming a fashion designer. With the financial assistance of his father, and the practical assistance of his sister, he established his own house, and ultimately became dressmaker to Queen Elizabeth II, among other royal and noble ladies.

It's popular to sneer at Hartnell, to call his clothes "dowdy" and "frumpish", but that's really wrong. Much of his work, particularly his evening wear, could, to the contrary, be called "over-the-top", with embellishments of jewels, fur and heavy embroidery. Indeed, he is quoted as saying, "For me, simplicity is the death of the soul." While his daywear for the Queen has been deemed "matronly", one must not forget that, when she was young, it was common for young, married women to dress in an older style. And Hartnell also talks about the various constraints that exist when designing for royalty: the use of pale colors to stand out in a sea of people wearing darker colors, a design that allows for the wearing of Orders, the need to "set an example" (as with wartime restrictions). As he puts it in describing the choice of colors for Queen Mary's visits to bombed sites, "Black does not appear in the rainbow of hope."

In many ways, Hartnell put English fashion design on the map. Most people would be hard-pressed to name an English fashion designer before Hartnell. There is, of course, Charles Worth, but he made his name in Paris. After Hartnell, the names keep coming: Mary Quant, Zandra Rhodes, Vivienne Westwood and so on.

This memoir is a must for anyone interested in fashion history, whatever their opinions of Hartnell's designs.

The Things

Norman Hartnell left Cambridge without a degree, intent on becoming a fashion designer. With the financial assistance of his father, and the practical assistance of his sister, he established his own house, and ultimately became dressmaker to Queen Elizabeth II, among other royal and noble ladies.

It's popular to sneer at Hartnell, to call his clothes "dowdy" and "frumpish", but that's really wrong. Much of his work, particularly his evening wear, could, to the contrary, be called "over-the-top", with embellishments of jewels, fur and heavy embroidery. Indeed, he is quoted as saying, "For me, simplicity is the death of the soul." While his daywear for the Queen has been deemed "matronly", one must not forget that, when she was young, it was common for young, married women to dress in an older style. And Hartnell also talks about the various constraints that exist when designing for royalty: the use of pale colors to stand out in a sea of people wearing darker colors, a design that allows for the wearing of Orders, the need to "set an example" (as with wartime restrictions). As he puts it in describing the choice of colors for Queen Mary's visits to bombed sites, "Black does not appear in the rainbow of hope."

In many ways, Hartnell put English fashion design on the map. Most people would be hard-pressed to name an English fashion designer before Hartnell. There is, of course, Charles Worth, but he made his name in Paris. After Hartnell, the names keep coming: Mary Quant, Zandra Rhodes, Vivienne Westwood and so on.

This memoir is a must for anyone interested in fashion history, whatever their opinions of Hartnell's designs.

The Things

97. The Little Guide to Vintage Shopping: Insider Tips, Helpful Hints, Hip Shops, by Melody Fortier

This little book is an excellent guide for anyone who is interested in vintage clothing, whether it be to wear or to collect. Fortier provides many useful tips for buying in a variety of stores, online or at auction, and she clearly knows what she is talking about.

While no one book can make you an expert at identifying vintage clothing and materials, this is a fine start. Fortier discusses how to date clothes by the type of closures and the labels, how to determine what fabric a garment is made of, what construction to look for, general rules of pricing and how to care for your vintage find. I appreciated the sections devoted to hats, shoes and other accessories, because, as a self-styled "accessory queen", I believe that these items lend the finishing touch to any outfit. That pair of vintage gloves gives a certain "je ne said quoi" to any modern suit.

One area that I haven't seen mentioned in other books on the subject is "reinventing" vintage. If a garment is damaged, or a very common style, Fortier sees nothing wrong with customizing and updating it, and shows several examples.

The only real quibble I have is that I would have liked more illustrations to supplement descriptions of technical terms. But overall, this is definitely a book I'd recommend for inclusion in the library of anyone with a serious interest in buying vintage fashion.

This little book is an excellent guide for anyone who is interested in vintage clothing, whether it be to wear or to collect. Fortier provides many useful tips for buying in a variety of stores, online or at auction, and she clearly knows what she is talking about.

While no one book can make you an expert at identifying vintage clothing and materials, this is a fine start. Fortier discusses how to date clothes by the type of closures and the labels, how to determine what fabric a garment is made of, what construction to look for, general rules of pricing and how to care for your vintage find. I appreciated the sections devoted to hats, shoes and other accessories, because, as a self-styled "accessory queen", I believe that these items lend the finishing touch to any outfit. That pair of vintage gloves gives a certain "je ne said quoi" to any modern suit.

One area that I haven't seen mentioned in other books on the subject is "reinventing" vintage. If a garment is damaged, or a very common style, Fortier sees nothing wrong with customizing and updating it, and shows several examples.

The only real quibble I have is that I would have liked more illustrations to supplement descriptions of technical terms. But overall, this is definitely a book I'd recommend for inclusion in the library of anyone with a serious interest in buying vintage fashion.

98. The Classic Ten: The True Story of the Little Black Dress and Nine Other Fashion Favorites, by Nancy MacDonell Smith

One need not consider it necessary to own all of Smith's "classic ten" to agree that they are, indeed, classics. Many women lead happy and fulfilled lives never having put on a pair of jeans or sneakers. Others wouldn't dream of letting a pair of high heels into their closet, and many simply cannot afford pearls or cashmere sweaters. Nevertheless, the history of all these items makes for a fun read.

Smith not only discusses where these items originated and how they developed, but also describes their place in popular culture, particularly film (such as Audrey Hepburn's iconic little black dress in Breakfast at Tiffany's or Lana Turner's image as "the Sweater Girl").

But somebody needs to tell her that Harriet Vane was never Peter Wimsey's "paramour"!

One need not consider it necessary to own all of Smith's "classic ten" to agree that they are, indeed, classics. Many women lead happy and fulfilled lives never having put on a pair of jeans or sneakers. Others wouldn't dream of letting a pair of high heels into their closet, and many simply cannot afford pearls or cashmere sweaters. Nevertheless, the history of all these items makes for a fun read.

Smith not only discusses where these items originated and how they developed, but also describes their place in popular culture, particularly film (such as Audrey Hepburn's iconic little black dress in Breakfast at Tiffany's or Lana Turner's image as "the Sweater Girl").

But somebody needs to tell her that Harriet Vane was never Peter Wimsey's "paramour"!

I enjoyed this post. I like the look of the book about Vintage Shopping. It sounds like a useful resource and something to inspire interest in Vintage fashion.

ReplyDelete