55. The Man Who Loved Books Too Much: the True Story of a Thief, a Detective, and a World of Literary Obsession, by Allison Hoover Bartlett

There are many kinds of book collectors. Some collect a particular author or subject matter, some incunables and others modern first editions. Most are rational, law-abiding citizens. But sometimes the urge to collect becomes an obsession, as with Sir Thomas Phillipps' desire to own a copy of every book in the world. (I highly recommend A.N.L. Munby's Portrait of an Obsession, a distillation by Nicolas Barker of the five volumes of Phillipps Studies.) And sometimes, as with John Gilkey, the subject of Ms. Bartlett's book, it causes the collector to turn to crime.

Gilkey was (is?) a book thief. He seems to have wanted books, not for their content, but to have them, to possess them as physical objects, and as a signifier of taste. But, not having the money to build his collection, he took the view that he had a right to have a collection and that, if book sellers charged more than he could afford, he could simply take them. He gathered, often through retail jobs, credit card information, and used this to purchase books.

Bartlett juxtaposes Gilkey's story with that of Ken Sanders, a book seller and one-time chair of the Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America security committee, who became as obsessed with hunting down Gilkey as Gilkey was with hunting down books to steal.

Bartlett conducted extensive interviews with both, and one of the most interesting aspects of this book is the way its writing caused the author to become a bit obsessed herself, not so much with books, though she feels a bit of temptation herself, but with the story. She goes with Gilkey, during a time when he was not locked up, to a store from which he had stolen in the past. He reveals to her certain information, and she struggles over whether to pass it on, knowing that, if she does so, he might close his mouth to her and affect her ability to write her book.

There are those who, looking at my double-shelved bookcases, and the piles of books on my floor and most flat surfaces in my apartment, would call me a woman who loves books too much. I feel what Bartlett terms the "sensory enticement" of books, enjoy the feel of a heavy paper with deckle edge, the smell of a leather binding, the heft of a volume in my hand. But I cannot fathom stealing a book, however tempted, and would say, with the medieval scribe, that a book thief should have "his name be erased from the book of the living and not be recorded among the Blessed".

The book is well-written and well-researched (though I noted a couple of errors in legal procedure, these are minor in relation to the book as a whole), and is sure to please all who love books, detective stories, and the psychology of obsession.

56. Bibliomania: a Tale, by Gustave Flaubert

This small volume from the Rodale Press contains the short story by Flaubert, based upon the true story of a monk who, upon the dispersal of his monastery's library, set himself up as a bookseller in Barcelona. When a rival book dealer outbid him for a unique volume, the rival's home burned down and the man's body was found in the ruins. When the book was found in Don Vincente's home, he was charged with the murder and confessed to it, and others - all people who had bought books from him, books that he could not bear to lose. At his trial for murder, his counsel argued against the alleged motive, contending that the book was not, in fact, unique. This revelation upset DonVincente more than being convicted and sentenced to death!

Flaubert's tale does not follow Don Vincente's story exactly. Some of the alterations he introduces create a very different sort of character of his protagonist. Giacomo, the former monk, was not a librarian. Indeed, he can barely read. His obsession is for books as objects: "He loved a book because it was a book; he loved its odour, its form, its title". His desire for the unique book is "to have it for himself, to be able to show to all Spain, with a smile of insult and pity for the King, for the princes, for the savants, for Baptisto, and say: 'Mine, this book is mine!' and to hold it in his two hands all his life, to fondle it as he touches it, to take in all its fragrance as he smells it!"

There is a twist at the end of Giacomo's trial that shows how far a man may go to ensure that he and he alone owns a book.

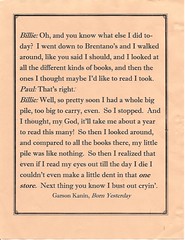

The Rodale Press edition has suitably spooky illustrations by Arthur Wragge (one accompanies this review). Unfortunately, the translator is not identified.